Looking Back On Helm

A summary with reflections and lessons learned on the journey of building Helm, a venture-backed startup that developed consumer privacy and security products

Helm was a venture-backed startup I co-founded and ran as CEO starting in 2016. We shut down the Helm service at the end of 2022. With time to reflect on the last seven years building Helm, I have summarized the journey and reflected on some lessons learned in case it may benefit other founders, investors or operators working on similar problems.

Why We Started Helm

We started Helm to address an unsolved problem. After the Snowden revelations, we expected new products that provided necessary levels of privacy for consumers by putting them back in control and ownership of their data. While the resulting widespread deployment of encryption with Let’s Encrypt shored up some exposure, it underscored an implicit acceptance that cloud providers should have access to consumer data. In the US, third-party doctrine meant the government could get access to consumer data without a warrant and we did not see a product for consumers that allowed them to opt out of both big tech and the government’s reach. So in 2016, my co-founder Dirk Sigurdson and I set off to reimagine how we could continue living our lives online but without the trade on privacy that has eroded trust on the internet.

Helm’s Product

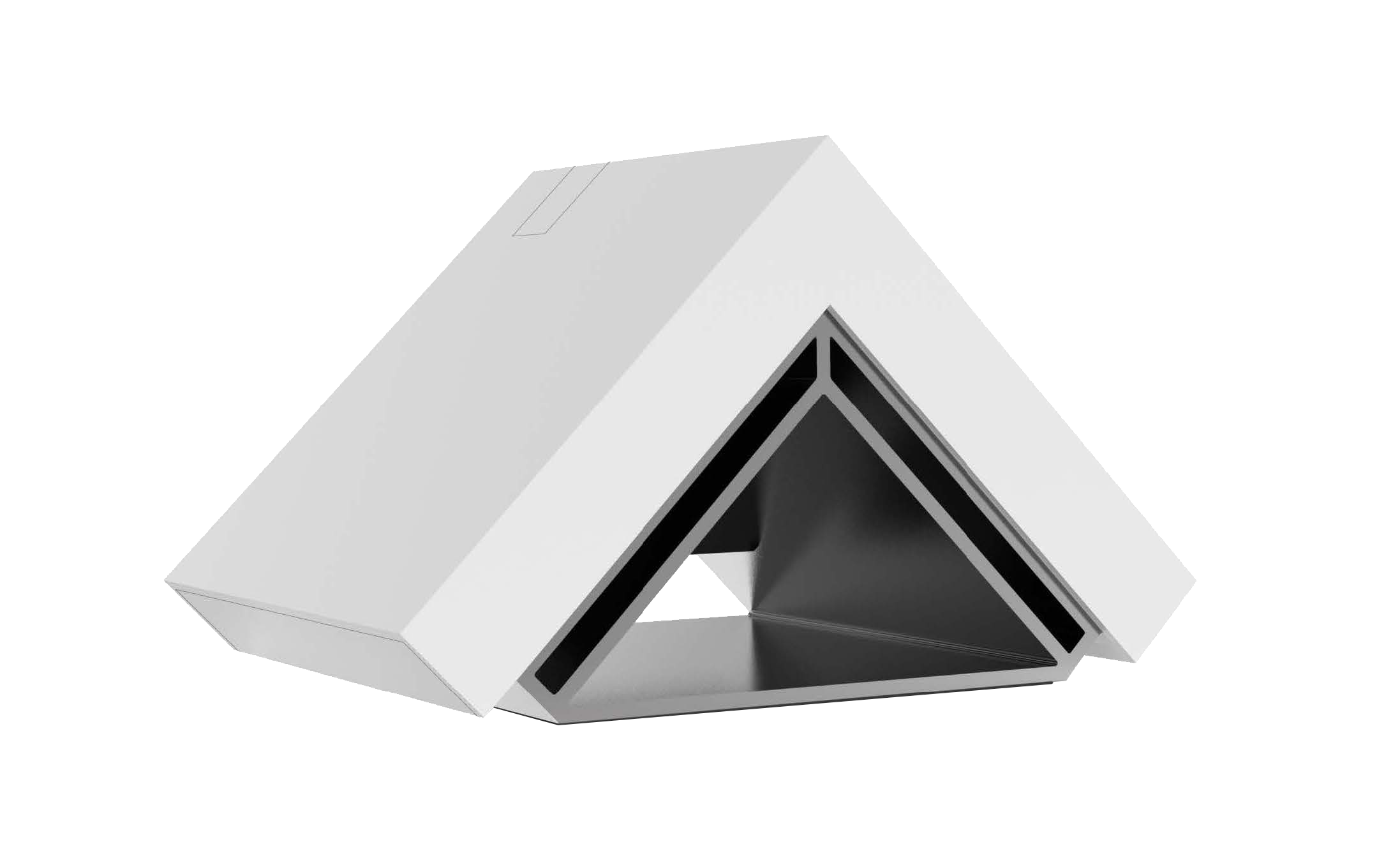

Helm’s product was a secure personal server combined with a cloud-based service that made it incredibly easy to own your data — starting with online identity and email. In less than 5 minutes, you could set up Helm in your home with a custom domain and have email, calendar and contact services that work with all of your devices and are accessible from anywhere in the world. We carefully designed Helm over years to be secure and private from the silicon up and to leverage a cloud-based service for a plug and play network setup experience.

Our Journey with Helm

A lot went into building Helm. Hardware startups are exponentially more complex than software startups. I have captured a summary of the key phases of the company, of which product development, manufacturing, brand and go to market all ran in parallel. Interspersed through this summary are some relevant lessons learned (click to expand).

Formation and Seed Funding

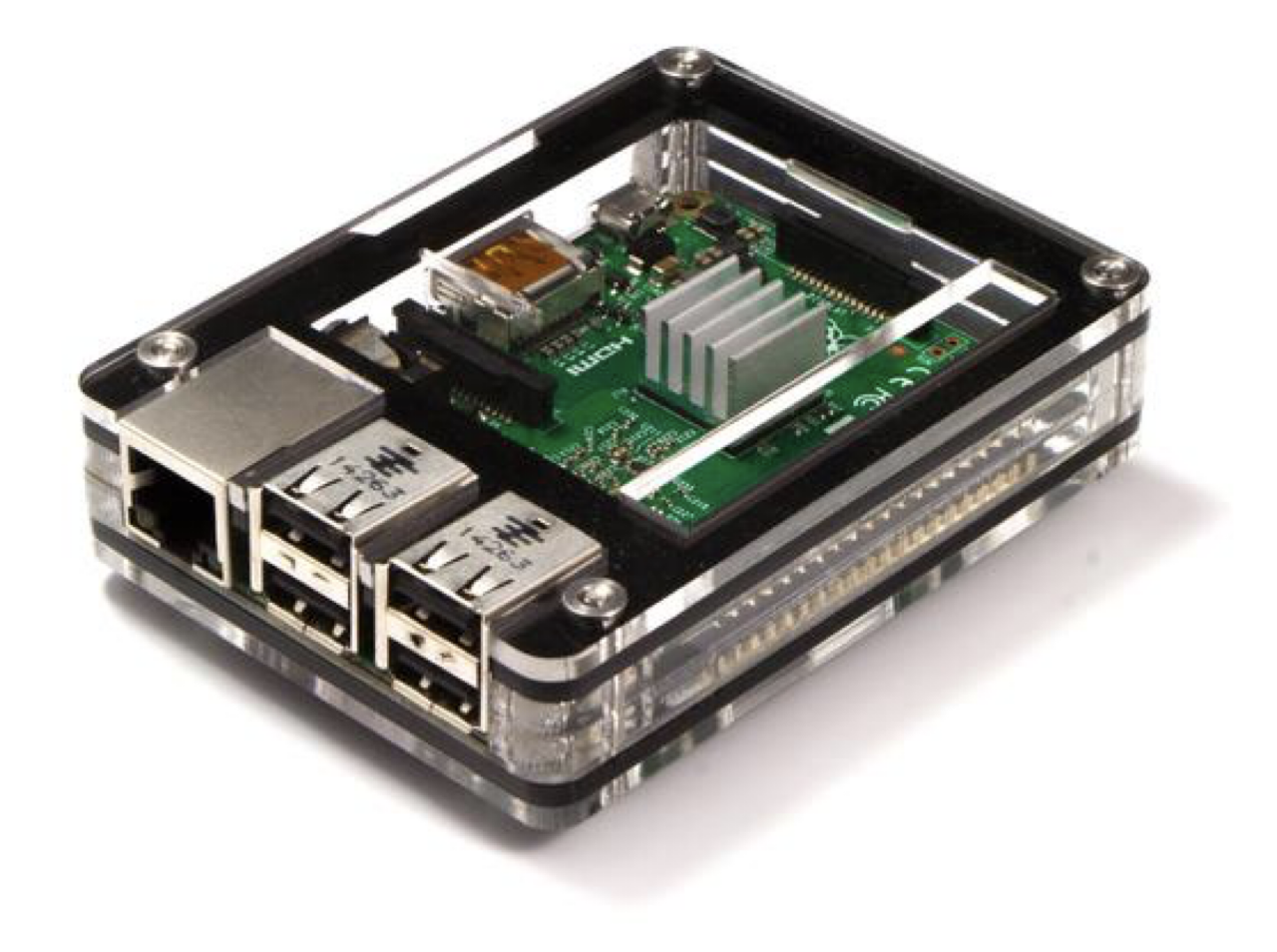

My co-founder and I bootstrapped Helm in 2016. We prototyped a product using off the shelf hardware like Raspberry Pis, and discovered a market by meeting with prospective customers at privacy/security events and a Maker Faire. We also conducted market testing using surveys and landing pages. We learned that a relatively technical early adopter segment along with a mass market segment shared privacy concerns and expressed strong purchasing intent for our product.

💡 Build Your Community Early

We had an opportunity to build our community early, well in advance of launching our product as we started prototyping nearly 2.5 years before the product launched. Consumer privacy was an issue of growing importance in 2016 and we missed an opportunity to capture an audience concerned with privacy by putting out interesting and helpful content. Growing a mailing list to 10k+ pre-launch for most products should be table stakes these days for a startup.

We raised a $4m seed round in 2017 led by Garry Tan and Initialized Capital. The goal with the funds was to design, develop and manufacture a v1 product priced at $199 with support for a core email use case. We also needed to gain enough traction to raise a subsequent round of funding. We set out to build a great team, get to $1-2M in sales with the first few thousand customers, and go raise series A to scale beyond early adopters to a broader mass market audience.

💡 Make Exceptions for Rare Talent

Shortly after we had closed our seed round, we had an opportunity to bring onboard an incredible world-class design and product talent. This individual would have been a force multiplier to have on the team and was keen to join as a co-founder with a significant equity stake. Having just spent a year bootstrapping the company and recently closing a round of financing, the amount of equity felt too rich at the time. Our founder egos got in the way and, in hindsight, it may have been penny wise, pound foolish. The equity we saved wouldn't have had a material impact on the business or our outcomes in relation to the impact this individual would have had. When there are so few people in the world at that level, make an exception and do what it takes to bring them onboard.

💡 Expect Recruiting To Always Be Hard

After we raised our seed round, we thought recruiting was going to be easier than it was for our first startup. We built an amazing team at our first startup and thought we would do even better the second time around with ease. After all, we had a successful exit, an IPO and some of the best investors supporting Helm - lots of people should be interested to work with us, right? As it turned out, those factors helped with closing candidates but not with getting applicants. We did not appreciate how much the market for talent and compensation had changed in just 5-6 years.

Product Development

After evaluating various chip platforms and board design firms, we hired the reference board design team for our preferred SoC (system-on-chip). We believed this choice would lower risk and shorten time to market despite higher fees. Unfortunately, the opposite occurred as it took longer due to a design flaw with memory and it also cost more than expected. Instead of the electrical BOM coming in at $100 as specified in the requirements, it came in over $300. This proved to be a significant issue.

💡 Get concrete about investor support through difficult decisions

When it became clear that the v1 cost would drive us to price it well north of what we intended ($499 vs $199), we became pretty concerned. This was something we discussed in depth as a board and we contemplated many options, including going back and revising the hardware design to correct the cost issue. Ultimately we decided to continue after a belief an investor shared resonated: early adopters are not particularly price sensitive. Our market research supported this belief as well. In that moment, we were all struck with confirmation bias. If I could go back and revisit that time in the business, I would have gone deeper on the idea of revising the hardware design to address cost.

I ruled it out quickly initially because of the amount of time and corresponding burn it would entail, putting us in an impossible situation to raise further financing from a new investor. What I severely underestimated was the level of support and conviction of our existing investors. At that pivotal moment, I should have put together a plan with a timeline and cost to see about support for it from existing investors. Given the follow on financing we raised over the life of the company, the support would likely have been there. While it’s hard to say how much this would have affected Helm’s trajectory, I believe we may have gone back to first principles thinking for manufacturing and started in China with the v1. We could have had even faster growth with a lower priced v1 and, with proper unit economics, had a better overall story for the Series A.

We selected an industrial design firm with a great visual aesthetic. We held a core belief that a distinctive, beautiful industrial design would help with brand and market adoption. The intersection of a desire for a distinctive industrial design and long term extensibility also contributed to cost creep. We wanted the enclosure to cost under $10 and it came in well over $20 with the added wrinkle of creating additional manufacturing assembly costs.

Manufacturing

We initially considered a first principles approach to manufacturing our product but we decided to defer to investor advice to hire an operations consultancy. This consultancy discouraged us from pursuing China as an initial manufacturing destination due to our initial volumes. We ran a selection process to specify our manufacturing needs and screen potential partners for a fit. We selected a reputable Tier 1 contract manufacturer who shared our excitement about the market opportunity.

💡 Be selective about when to adopt a first principles approach

Stated slightly differently, a key determinant of founder success is figuring out which advice to ignore, which advice to follow and which advice to adapt to their business. In each area of the business, founders must decide whether to follow advice and best practices, or follow first principles thinking when it can contribute to increasing the likelihood of success. Startups do not have the luxury of first principles thinking for all areas of the business - there’s simply not enough time or resources. With Helm, we largely got our mix right with the exception of manufacturing the v1.

There is a subtle nuance with the general wisdom/advice that small initial volumes aren’t a good fit for China. I believe this is true when working with a larger contract manufacturer, however there are plenty of opportunities to work with partners there outside of that context as we discovered with the v2. This was a very successful product for us in critical dimensions - cost, margin, quality, scale. Covid-related restrictions in China were ultimately the undoing of that manufacturing model for us and for our business as well.

An unexpected re-org at the contract manufacturer exacerbated a mismatch between a Tier 1 contract manufacturer and an unproven startup. After they signaled their intent to drop our business by drastically increasing costs midway through a prototype build, the 2nd place finisher in our selection process became the go-forward option. This smaller, Tier 3 contract manufacturer also proved to be an unethical partner, holding our first production manufacturing run hostage midway in order to extort additional payment from us. We had heard of these nightmare scenarios happening to other startups, and there is typically no leverage so there’s no choice but to pay up. This made our unit economics upside down where we lost money on early units priced at $499, something not uncommon in hardware product cycles.

Brand and Go To Market

When we started the company, we had a placeholder name. We spent a good bit of time and money on developing a consumer brand. Some tend to think of brand as the visual identity: logo, colors, fonts, etc. While we did go through a process with a brand agency to define those aspects, we also spent time on what I think is more essential to defining a brand - its name, values, attributes and ultimately how you show up for your customer with the experience you create for them.

Our go to market plan consisted of experiments with paid search, podcast ads and PR. Podcast ads were our most effective paid advertising lever. Podcasts that were interested in having us as guests and reviewing our product for their audience proved to be the best advertising options as well. Paid search was not particularly effective for us. We found product reviews to be extremely successful in driving growth. We also leaned heavily into PLG, with an email footer for all emails sent from Helm linking to a comparison of Helm with other hosted email services. We also leveraged word of mouth with the launch of a referral program for our v2.

Fundraising and Helm V2

Our Series A fundraising process was not successful despite a repeatedly sold out product and > $1M revenue run rate. Going out to raise in the wake of a consumer hardware startup fire sale hurt our prospects though we still got to five partner meetings. We ultimately didn’t get a term sheet because of concerns about market size and unit economics. Some firms were consensus driven and we found that there is no consensus about the market opportunity for consumer privacy and security. Otherwise, the partner leading the deal opportunity didn’t have the seniority or internal social capital to get the deal across the finish line.

💡 Early stage fundraising for hardware startups is particularly hard

Hardware is extremely polarizing for venture capitalists. There aren’t enough examples of consumer hardware startups that reached great heights independently and there have been a lot of flameouts even after raising massive amounts of capital (and even after an IPO - see Peloton). The bar is much higher for raising capital and my advice to hardware founders I meet with now is to either get to break even before raising or have a clear path to do so after the initial round because there may never be any more capital for your business until you don’t need it. This is much harder for a hardware startup than a software-only startup to accomplish but them’s the breaks these days. It’s better to go in eyes wide open than waste precious time.

We considered crowdfunding for Helm at various points before launching our v1 product. I was reluctant to do this for a number of reasons. Many supporters of crowdfunding projects were shortchanged by projects that failed to live up to their timelines and promises. Many crowdfunded projects also didn’t seem to have much staying power - the founders may have shipped one product but didn’t build a more durable business along the way. These perceived attributes about crowdfunding turned me off as I felt they would kneecap a brand focused on consumer privacy and security where trust is essential.

Without a new lead investor, we cut down our burn by doing layoffs and converting some employees to contractors. This allowed us to regroup and contemplate various paths forward: a hosted version, a downloadable version or go back to the drawing board and created a v2 hardware product. We decided to go all in on a v2 hardware product after some investigation showed us that we could hit our original price target of $199 with healthy margins.

We vetted a design and manufacturing partner more thoroughly with lessons learned from our v1 experience. We moved our supply chain out of Mexico and into China in January 2020, just before the global pandemic took hold. A 6-9 month development process for the v2 ended up taking 18 months due to slowdowns from the pandemic response in China. As we started getting inventory to fulfill pre-orders, our partner went dark on us and stopped engaging before completing the initial manufacturing run.

After trying all available levers, including offering additional payment, we accelerated plans to bring a second manufacturer online. They were doing a good job hitting key milestones with prototypes and EVT/DVT builds, which helped us build confidence about getting to break even/profitable. Unexpectedly they were delayed with the PVT build, so much so that the company’s cash position in relation to the rate at which we could turn over inventory started to become an issue. In October, we determined we were unlikely to catch up and notified customers we had to shut down the service by the end of the year.

Closing Thoughts

As a repeat founder, the upside is that the lows are not as low, but the highs are not as high either. It still takes a tremendous amount of dedication to manage your attitude and mental health, which I had varying degrees of success with over that time. A particularly challenging time occurred when we were working through our v1 production run, our contract manufacturer started to extort us for additional funds, we were dealing with a significant bug, a close family member was diagnosed with a potentially fatal health condition and fundraising wasn’t going well. It was a dark time and I wondered how to make it to the other side.

An aspiration for founders is to not tie up their identity and sense of self with their companies but this is easier said than done. It can feel impossible to sandbox your emotional wellbeing when you give everything you have and care deeply about the outcome. I found it’s critical to lean on those closest to you for support like your partner, family, co-founder, friends, and investors. These relationships will also get stress tested the most on the journey. I’m really fortunate to have a great working relationship with my co-founder Dirk over the last 14 years. We’ve been there for each other through it all and I couldn’t have done any of it without him.

Seven years is a long time to work on a venture that doesn’t pan out. Usually, it’s easy to see if it’s working or not within the first few years. We continued on for so long because of some combination of perseverance and time distortion. Customers loved the product but we were supply constrained with the v1. We didn’t want to give up knowing we could fix what didn’t go well with the v1. I expected that within a year of kicking off the v2, we would know if things were going to work out. Instead, we entered this very strange period with the pandemic where the passage of time felt simultaneously very slow and very fast.

I want to thank our investors for their support. They were all helpful, humble and decent. Critically, they challenged me when needed. I want to call them all out: Garry Tan (Initialized), Eric Klein/Helen Boniske/Tim Skowronski (Lemnos), Chris Howard (Fuel), Geoff Entress, Hansmeet Sethi, Mike Miller (Liquid 2), Pat Gallagher (Tuesday), Steve Jang (Kindred), Stephen Francis/Neil Sirni (Arrive), Steve Garrity, Lee Linden (Quiet), Balaji Srinivasan, Nick Weaver, HD Moore, Jeff Fagnan/Sarah Downey and Jesse Proudman.

In particular, I want to thank Garry Tan who joined our board and supported the company through thick and thin. I also want to thank Todd Hooper who has been an incredible friend and sounding board over the years.

I want to thank my family and my friends for the support and understanding they have provided me over the years. No founder is an island and, though our experience is a lonely one, we remain a part of the main.

Lastly, I want to thank Helm's customers. I learned so much from you and appreciate your enthusiasm and support over the years. I'm sorry we weren't able to build a long term sustainable business to deliver on our vision.

As for what’s next, I have something lined up that I’ll be starting soon. I will be taking a break from the founder/CEO role and joining a team with a vision and mission that I’m excited about. I also expect to be more actively engaging with startups and investing along the way.

Thanks to Garry Tan, Dirk Sigurdson, Todd Hooper, Hansmeet Sethi and Ben Juhn for reviewing this and providing feedback.